—

“Everyone is a dancer” – Dance becomes art. Part 1: Beginnings

During the great social and artistic upheavals around 1900, one genre took on a whole new significance: modern dance, which developed into an independent artistic discipline. It not only freed the body from the corset and the classical-traditional step combinations of ballet. Movement is now allowed to be more than just the highest technical mastery of the body, namely subjective, emotional and free.

Under the heading “Dance becomes art”, the Edwin Scharff Museum highlights the many facets of artistic dance in two exhibitions.

The first deals with the preconditions and beginnings in the period from 1892 to around 1914.

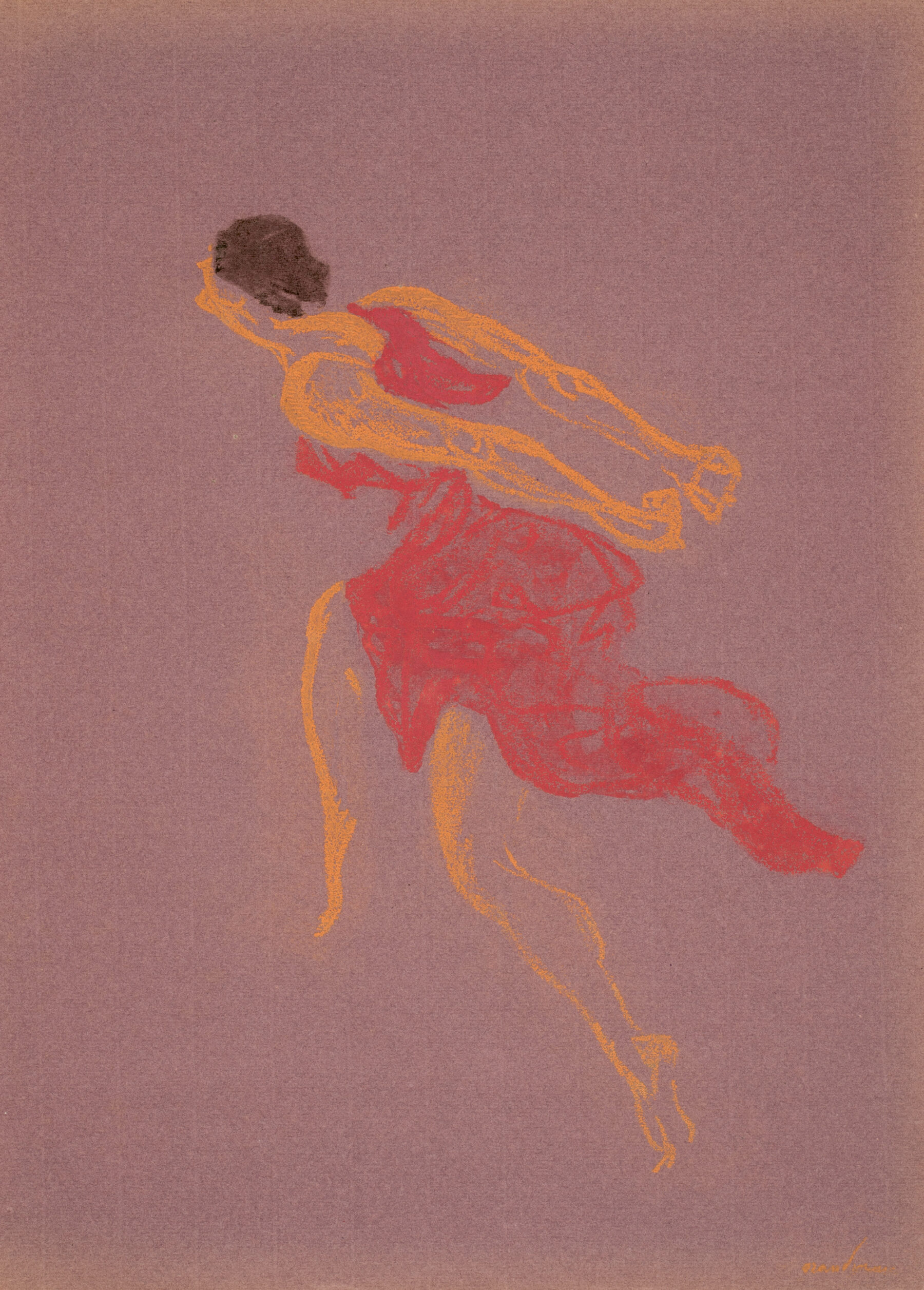

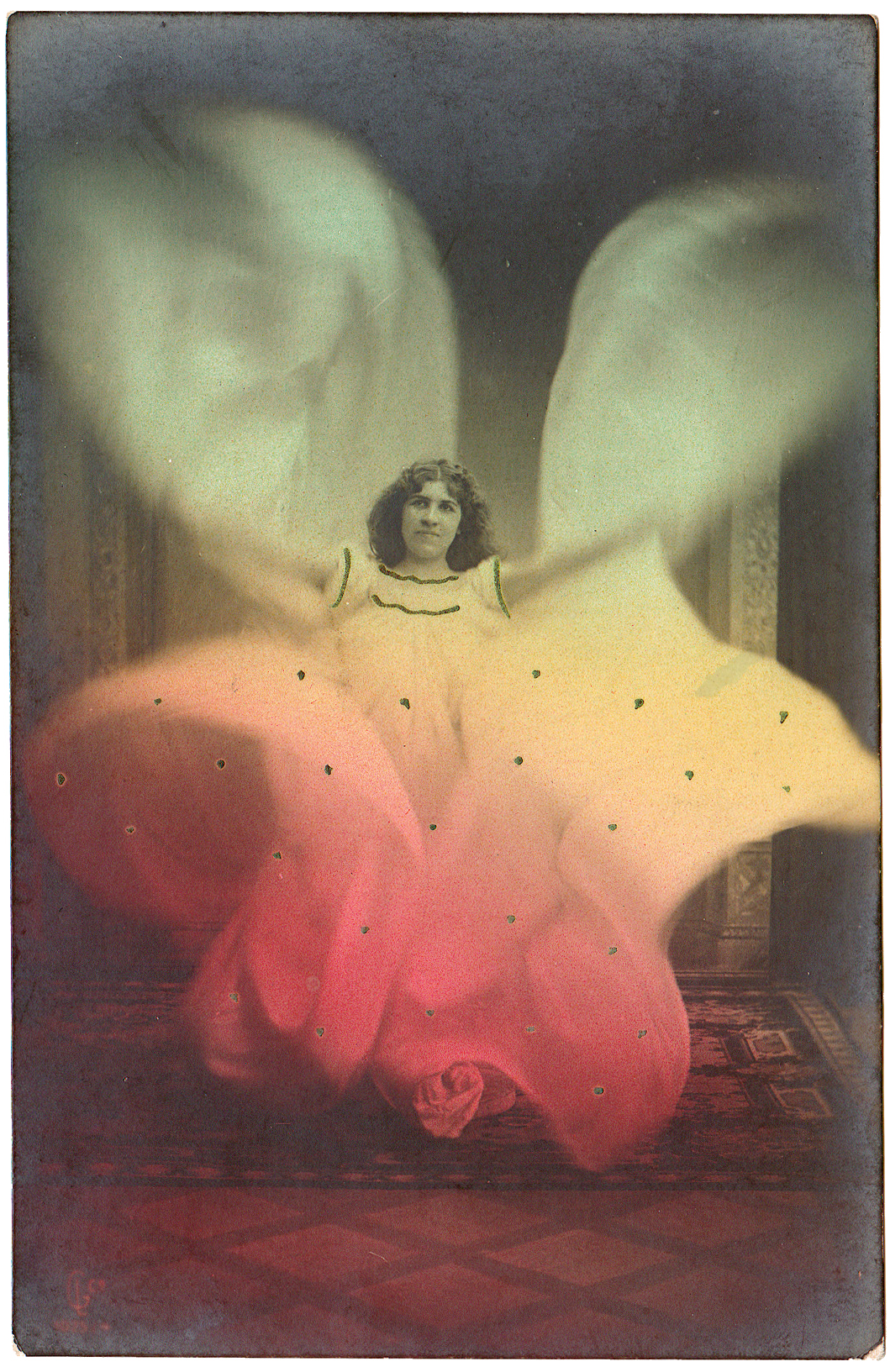

Above all, it was women who developed their own choreographies, brought their feelings to the stage and became independent entrepreneurs. For them, it was also a fight for independence and social participation. Loïe Fuller’s spectacular dance performances in Paris in 1892, with their synthesis of art and science and their proximity to Symbolism and Art Nouveau, marked the beginning of the new dance movement.

Soon afterwards, Isadora Duncan’s return to naturalness broke with social conventions. Grete Wiesenthal, on the other hand, played a central role in the reinvention of dance pantomime. Like all areas of art, non-European cultures also inspired dance and gave rise to new forms of design, such as Ruth St. Denisʼ and Sent M’Ahesaʼs exotic interpretations or Gertrud Leistikowʼs expressive mask dances. “Everyone is a dancer” – this was the motto that summarized Rudolf von Laban’s dance teaching. Like his colleague Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, he wanted to use free dance to reform society as a whole. The extent to which modern dance was anti-academic is shown by the positions of Vaslav Nijinsky, who fascinated audiences with his androgynous charisma, or the naturalness with which Alexander Sacharoff and Clotilde von Derp swapped gender roles.

There was a mutually beneficial dialog between the new dance and the visual arts. The new body awareness that developed in the field of tension between the most diverse reform movements is reflected in photography, film, graphics, painting, sculpture and fashion through a radically different formal language.

The Edwin Scharff Museum traces the new body expression in over 140 exhibits from all disciplines and the accompanying publication – and thus the event: dance becomes art.

We would like to thank our lenders!

Curator: Dr. Ina Ewers-Schultz

The exhibition is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue, which is available in the museum shop (Price: €24.95).

The special art exhibition area and the Collection Scharff will be closed from 23rd June to 5th December 2025 due to renovation work.